What Causes Shoulder Pain?

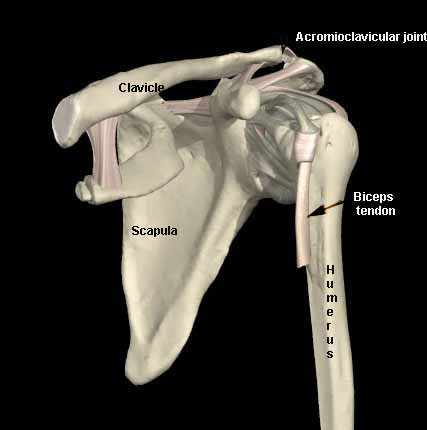

The shoulder joint is a complex structure composed of intricate bony architecture and a system of muscles, tendons, and ligaments. The “shoulder joint” is a combination of 4 articulations — the glenohumeral (GH) joint, acromioclavicular (AC) joint, sternoclavicular (SC) joint, and the scapulothoracic (ST) articulation. These structures work together to provide the shoulder complex with multiple degrees of freedom, which allow the upper extremity to be abducted, adducted, rotated, flexed, and extended.

Several factors should be considered in evaluating the painful shoulder. The evaluation may not consist of a single diagnosis but rather multiple interrelated diagnoses, such as acromioclavicular pain and impingement.

Some problems are activity specific. For example, throwing injuries may result in different types of injuries than contact injuries or lifting injuries. In athletic or work-related injuries, more than one physical examination (PE) may be required to detect changing pain patterns and the physical examination must be correlated with diagnostic studies.

A thorough clinical evaluation of the entire shoulder girdle coupled with a knowledge of relevant anatomy, medical history, clinical tests, and a complete problem focused physical examination can enable a physician to work through the algorithm for diagnosis and treatment of shoulder injury and pain.

Since cervical spine pathology can refer pain to the shoulder and even result in weakness of the shoulder, an examination of the cervical spine, including a motor, sensory and reflex assessment may be necessary.

Anatomy of the Shoulder

What is the Glenohumeral Joint?

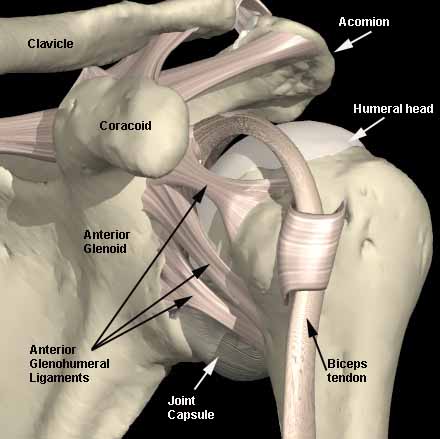

The glenohumeral articulation has classically been described as a golf ball on a golf tee. Only 30% of the humeral head articulates with the glenoid at any one time. Although this contact surface is greatly increased by the labrum, the glenohumeral joint is inherently unstable. The joint relies on static (ligaments and tendons) and dynamic (muscular contractions) stabilizers. The glenohumeral joint is responsible for the majority of motion in the coronal plane. For every 3° of abduction, 2° occur in the glenohumeral joint and 1° at the scapulothoracic articulation.

What is the Sternoclavicular Joint?

The sternoclavicular joint is a diarthrodial joint whose articular surfaces are covered with fibrocartilage; it is a saddle-type joint, freely movable and functioning like a ball-and-socket joint. This joint is relatively incongruous and relies on multiple ligaments for stability. These ligaments include the intraarticular disk ligament, costoclavicular ligament, capsular ligament, and interclavicular ligament. Almost all motion of the upper extremity is transferred proximally to this joint. It can be dislocated from injury or can cause pain due to arthropathy.

What is the Acromioclavicular Joint?

The acromioclavicular joint is a diarthrodial joint whose articular surfaces are covered with hyaline cartilage, interposed with a fibrocartilaginous disk. Horizontal stability is provided by the capsular ligaments, mainly the superior acromioclavicular ligament. Vertical stability is provided by the coracoclavicular ligaments, the conoid and trapezoid ligaments.

What is the Scapulothoracic Articulation?

The scapulothoracic articulation consists of the scapula articulating with the bony thorax with a bursa interposed.

Motion is controlled by a group of muscles that includes the rhomboid major and minor, levator scapulae, serratus anterior, trapezius, omohyoid, and pectoralis minor. Disorders of these muscles can present as scapular winging or dyskinesia of the scapulothoracic articulation.

What is the Rotator Cuff?

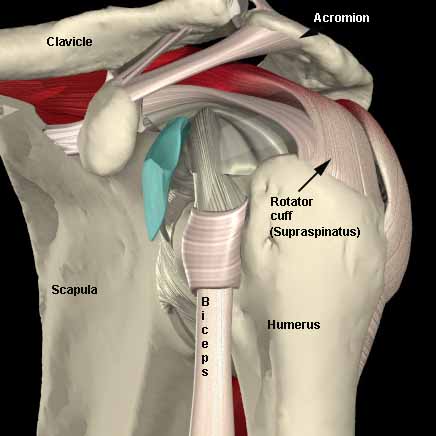

The rotator cuff is composed of 4 muscles — the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis. The tendons of supraspinatus (labeled below), infraspinatus, and teres minor insert into the greater tuberosity of the humerus; the subscapularis inserts into the lesser tuberosity. When a tear of the rotator cuff occurs, it is most commonly the supraspinatus that is torn. The infraspinatus and teres minor tendons can be affected if a large tear propagates posteriorly. Less frequently, these tendons can be torn independently.

Shoulder Labrum, Ligaments, and Biceps Tendon

The glenohumeral joint is encased by a thin, lax, fibrous capsule. Anterior thickenings in the capsule — referred to as the superior, middle, and inferior glenohumeral ligaments — along with the glenoid labrum, are the main static stabilizers of the glenohumeral joint. The labrum functions to increase the surface area of the glenoid, enhances its stability, and is the fibrous attachment of the glenohumeral ligaments to the glenoid. The biceps tendon is anchored to the superior glenoid via the superior labrum and is commonly referred to as the biceps labral complex.

What is the Coracoacromial Arch?

The coracoacromial arch is formed by the acromion, the coracoacromial ligament, and the coracoid process. The main structure of the arch is the coracoacromial ligament, which is intimately involved in subacromial impingement syndrome.

How to Obtain a Clinical History for Shoulder Pain

In obtaining a history, the examiner should be aware of other pertinent facts such as general health status, previous injuries and conditions and prior treatments.

Then the more specific details of what, how, when and where can be investigated.

- What is the problem area to be evaluated?

- What makes the problem better or worse?

- How did the problem develop?

- How has it been treated so far?

- When did the problem develop?

- Where did the problem occur?

Additional information regarding patient age, handedness, occupation, marital status, domestic status (i.e., does the patient live alone?), leisure activities and sports involvement are important. This information may provide additional insight into the problem.

Concurrent medical or genetic conditions are important factors as well. Patients with diabetes will have a more refractory course with adhesive capsulitis, while individuals who are voluntary dislocators may have a psychiatric history that could complicate treatment.

Important factors in the patient’s history

All Patients

- Age

- Hand dominance

- Occupation

- Injury?

- Injury mechanism

- Length of time symptoms

Shoulder Patients

- Overhead use — athletics/repetitive work

- Night pain

- Radicular symptoms

- Neck pain

- Any injections and location?

- Specifics rehabilitation?

- Surgery? (need operative dictation)

Some of the more common subjective patient complaints are listed in the table below.

Impingement (Stage I)

- Intermittent mild pain with overhead activities

Impingement (StageII)

- Mild to moderate pain with overhead or strenuous activities

Impingement (StageIII)

- Pain at rest or with activities

- Night pain may occur

- Weakness is noted

Rotator cuff tears (Full thickness)

- Classic night pain

- Weakness noted predominantly in abductors and external rotators

- Loss of motion

Adhesive capsulitis (Frozen shoulder)

- Inability to perform activities of daily living due to loss of motion

- Loss of motion may be perceived as weakness

Anterior Instability

- Apprehension to mechanical shifting limits activity

- Slipping, popping or sliding may present as subtle instability

- Apprehension usually associated with horizontal abduction and external rotation

- Anterior or posterior pain may be present

Posterior Instability

- Slipping or popping out the back

- This may be associated with forward flexion and internal rotation while the shoulder is under a compressive load

Multi-directional Instability

- Looseness of the shoulder in all directions

- Pain may or may not be present

Acromioclavicular (AC) Pathology

- Localized pain, swelling, deformity, tenderness localized to AC joint

How to Perform a Physical Examination for Shoulder Pain

Inspection

Inspection should be from all views and should note muscle mass and tone, deformities, scars, masses, bruising, discoloration and swelling. Symmetry of right and left sides should also be noted.

Inspection of the shoulder requires adequate visualization of the entire upper extremity, shoulder girdle, chest, and back. Examination is performed with the shirt off for male patients, and a sleeveless shirt for female patients. The examiner should inspect muscle tone, symmetry, and deformity, especially at the acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joints, shoulder, scapula, and clavicle. Scapular thoracic rhythm should be assessed from a posterior vantage point with the arms fully abducted.

Palpation

Palpation of anatomic landmarks is critical to determine sites of tenderness. The shoulder girdle should be palpated for warmth, tenderness, deformity and crepitus. Structures that should be examined include the cervical spinous processes, medial scapula, posterior rotator cuff, anterior rotator cuff, deltoid, AC joint, SC joint, coracoacromial arch and biceps tendon.

Range of Motion

The first step is to document active range of motion of the neck, including flexion, extension, lateral bending, and rotation. Next, assess active and passive range of motion of the shoulder. If active range of motion is full, passive range of motion tests do not need to be performed.

Ranges of motion that need to be documented are forward elevation (in the sagittal plane), abduction (in the coronal plane), and internal and external rotation.

Internal rotation can be documented by vertebral level according to how high up the back the patient can place his or her thumb. External rotation should be documented at both 0° and 90° of abduction. Generally speaking, forward flexion and abduction are 0° to 180°, internal rotation is to ~T5 to T7, and the arm will externally rotate to 45°.

Spurling’s Test

With Spurling’s test, the neck is positioned in lateral flexion and rotation with axial compression. Reproduction of radicular type pain to the ipsilateral side is a positive test. This position closes down the neural foramina, which compresses the cervical nerve roots as they exit the foramen. With a herniated nucleus pulposus or foraminal stenosis, this decrease in foraminal space is likely to reproduce radicular type pain.

Muscle Strength Testing

Muscle groups to concentrate on are the trapezius, serratus anterior, deltoid, and rotator cuff.

The deltoid is tested in forward flexion for the anterior third, straight abduction for the middle third, and in extension for the posterior third. The serratus anterior is evaluated by having the patient push off a wall while standing.

Winging of the scapula during this maneuver is classic when paralysis of the long thoracic nerve is involved. The supraspinatus can be tested by applying a downward force to the arms abducted 90°, forward flexed 30°, and internally rotated so that the thumbs are pointing down. The posterior cuff muscles (infraspinatus and teres minor) are evaluated by external rotation strength with the arm at the side and the elbow flexed to 90°. The subscapularis is tested by internal rotation strength with the arm in the same position.

Lift-Off Test

To test the function of the subscapularis muscle, the patient internally rotates and extends the arm so that it lies on the patient’s back — about the level of the waist line. The patient then attempts to lift the arm posteriorly away from the back. If this is not possible, then the test is considered positive. A modification of this test is to have the examiner hold the patient’s arm posteriorly away from the patient’s back. When the examiner releases the arm and the patient is unable to actively maintain this position, the test is considered positive.

Impingement Sign and Impingement Test

Impingement sign, commonly referred to as impingement syndrome, is a mechanical impingement of the rotator cuff between the coracoacromial arch and the humeral head. Anything that decreases the volume of this space can cause impingement.

Typically, calcifications in the acromioclavicular ligament and anterior acromial spur formation are the cause of impingement, which may or may not be associated with tears of the rotator cuff. Hypertrophy of the acromioclavicular joint secondary to arthritis has also been implicated in the cause of impingement.

Arm positions that cause the humeral greater tuberosity to impinge against the inferior aspect of the acromion will reproduce pain in patients with impingement syndrome.

Neer Impingement Sign

Neer described the impingement sign as the reproduction of pain with passive elevation of the arm. The examiner uses one hand to stabilize the scapula, while the other hand raises the patient’s arm in forced forward elevation with slight abduction. If pain is relieved after injection of 10 cc of 1% lidocaine into the subacromial space, then it is referred to as a positive impingement test.

Hawkins Impingement Test

The arm is elevated forward to 90° with slight adduction. The examiner then internally rotates the arm, which brings the greater tuberosity, rotator cuff, and biceps tendon under the acromioclavicular arch. If pain is elicited with this maneuver then it is considered a positive test for impingement.

Stability Testing

Instability patterns of the shoulder include anterior, posterior, inferior, and a combination of the 3 referred to as multidirectional. The examination is used to assess possible directions of instability and to correlate these with apprehension and symptom reproduction. It is performed with the patient upright and supine, both positions with the scapula stabilized.

For inferior instability, the arm is positioned along the side of the body and inferior traction is applied. A depression produced between the edge of the acromion and the humeral head is referred to as a sulcus sign.

To assess passive anteroposterior translation, the load and shift test is performed. First an axial load is applied to the humerus, which seats the humeral head in the glenoid fossa if there is inherent subluxation. The examiner then applies posterior and anterior stresses to the humeral head and attempts to translate the head out of the glenoid fossa.

After translation patterns are evaluated, symptom reproduction and apprehension with provocative maneuvers are assessed. To evaluate anterior apprehension of the left shoulder, the examiner stands behind the patient placing the left hand on the patient’s elbow. With the right hand, the thumb is positioned on the posterior humeral head to provide an anterior force while the fingers are placed anterior to help control any sudden instability. The arm is abducted to 90° with the elbow flexed. With increasing external rotation and forward pressure on the humeral head, the patient may express an apprehensive look, try to resist with muscular contractions, or simply state that the shoulder is beginning to dislocate. This is a positive apprehension sign. These maneuvers are repeated with the patient supine and with the edge of the table stabilizing the scapula. Again the arm is abducted to 90° and externally rotated while applying an anterior force. If apprehension or pain is encountered, then a posterior force is applied. If the apprehension and/or pain disappears, then it is a positive relocation test.

O’Brien’s Test for Superior Labral Anteroposterior (SLAP) Lesions

With the patient standing, the arm is forward flexed to 90° with the elbow straight. The patient adducts the arm 15° to 20° and fully internally rotates the shoulder so that the thumb is pointing down. The examiner then applies a downward force on the arm with the patient resisting. Next, the arm is externally rotated so that the thumb is pointing up. The examiner again applies a downward force to the arm while the patient resists. If pain is elicited with the thumb down and decreased or eliminated with the thumb up, then it is a positive test suggestive of a superior labral anteroposterior lesion.

Examination Overview

The major part of the physical examination is performed with the examiner facing the patient and dictating movement in a “Simon says” fashion. This seems to be the most reproducible way to get the patient to follow the movements desired.

When the examiner is looking for muscle asymmetry he needs to view the patient from the back to watch the movement of the scapula and shoulder. A male patient should have his shirt off, and a female patient should be wearing a sleeveless shirt or tank top. The first part of the examination is to duplicate active neck motion, which includes flexion-extension (chin on chest, chin all the way up), lateral rotation (chin on left shoulder, chin on right shoulder), and lateral bending (ear on left shoulder, ear on right shoulder). Abnormal motions could be caused by trapezius spasm, nerve root irritation (either from a narrowed foramen or herniated disk), or degenerative changes.

The examiner should then focus on active shoulder motion in forward flexion, abduction, external-internal rotation, and composite motions where the patient places an arm behind the back and then lifts the arm up and externally rotates it as if to throw a ball or to serve. If these motions are abnormal, passive range of motion of only the glenohumeral cavity is assessed.

If passive range of motion is normal, the deficits could be pain, rotator cuff tear, or nerve deficit or injury. If the passive range of motion is abnormal, results could be indicative of pain (the patient will not adequately relax), a frozen shoulder (adhesive capsulitis) or degenerative changes that would be observed on x-ray.

Finally, the examiner should perform a passive cross-arm adduction test, which pinches the subacromion space and is positive with impingement syndromes and also tests the acromioclavicular joint and is positive with acromioclavicular joint pain.

Proceed with palpation of anatomic sites. Begin with the sternoclavicular joint followed by the acromioclavicular joint and then the biceps tendon. In relatively thin individuals, the greater tuberosity can be palpated separately from the lateral edge of the acromion.

Next, observe rotator cuff strength and evaluate the subscapularis, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor muscles.

Test the subscapularis initially in internal rotation, the infraspinatus and teres minor in external rotation with the arm at the side, then the supraspinatus with the arm in the empty-can position. If rotator cuff strength is abnormal, this could be caused by pain (which can be evaluated by a diagnostic lidocaine test), or it could be weak because of an observed tear (which can be diagnosed by MRI or arthroscopy). A finding can be abnormal secondary to neurologic injury as a result of a nerve root, peripheral nerve, burner, or plexus injury.

Impingement signs are then evaluated. The two preferred methods are the Hawkins impingement test and the forced impingement test, which takes the elbow and gently forces the rotator cuff up against the lateral edge of the acromion. A positive test is indicative of pain, which suggests inflammation in the subacromion space. Determine whether this inflammation is tendinitis, bursitis, or a tear. Tendinitis or bursitis that is isolated would result in the remainder of the physical examination being normal or a proven lidocaine test.

Tears should be assessed whether they are partial or complete and can be evaluated by MRI or arthroscopy. Partial tears can be clinically significant in a competitive overhead or functioning overhead athlete, whereas in a non overhead athlete these tears may be clinically silent. The patient’s activity level should be factored into the decision for further diagnostic workup.

The final part of the examination evaluates glenohumeral instability and labral tears. This is the most difficult part of the examination and requires an extreme degree of skill on the part of the examiner as well as patient relaxation to determine if instability and/or labral tears exist. The patterns of instability that should be examined include anterior (with apprehension test), posterior (with a posterior drawer), and inferior (by applying a downward pressure on the arm). The position of instability by history as well as a physical examination and the component of multidirectional instability should be documented.

The table below demonstrates a stepwise approach for evaluating shoulder pain that begins at the neck, proceeds to the sternoclavicular, acromioclavicular, and scapulothoracic components of the shoulder joint, then focuses on particular anatomic sites, rotator cuff strength, and impingement signs, followed by glenohumeral tests. The physician should list all positive findings because multiple diagnoses are quite possible.

Cervical Spine Examination

- Abnormal findings

- Trapezius muscle spasm

- Nerve root symptoms

- Degenerative joint disease on examination or x-ray

- Other

- Continue assessment of cervical spine

- Normal cervical spine findings

- Proceed to shoulder assessment

-

Shoulder Assessment

- Abnormal active range of motion

- Normal passive range of motion

- Causes include:

- Pain

- Rotator cuff tear

- Nerve deficit

- Causes include:

- Restricted passive range of motion

- Causes include:

- Adhesive capsulitis (Frozen Shoulder), normal x-ray

- Degenerative joint disease, abnormal x-ray

- Pain due to impingement, AC arthritis

- Chronic dislocation

- Causes include:

- Normal passive range of motion

- Normal active range of motion

- Palpate for areas of tenderness to refine diagnosis

- SC joint

- Sprain

- Instability

- DJD

- AC joint

- Sprain

- Instability

- DJD

- Osteolysis

- Fracture

- Biceps tendon

- Impingement

- Tendinitis

- Adjacent labral injury

- SC joint

- Palpate for areas of tenderness to refine diagnosis

- Evaluate Rotator Cuff Strength

- Weakness

- Administer subacromial Xylocaine (Impingement test)

- Consider rotator cuff tear

- MRI may be warranted

- Neurologic injury

- Nerve root

- Burner

- No weakness

- Evaluate for subacromial impingement

- Weakness

- Impingement signs

- Positive

- Consider tendinitis or bursitis

- Treat with anti-inflammatory medications, activity modification, home exercises or physical therapy

- Possible rotator cuff tear- partial or complete

- Evaluate with MRI or arthroscopy

- Consider tendinitis or bursitis

- Negative

- Consider glenohumeral instability or glenoid labrum tear

- Positive

- Glenohumeral instability / Labral tests

- Instability

- Anatomic lesion confirmed by physical exam, x-ray, MRI, Examination under anesthesia, arthroscopy

- Anterior

- Posterior

- Inferior

- Multi-directional

- Functional instability

- Internal impingement

- Secondary impingement

- Anatomic lesion confirmed by physical exam, x-ray, MRI, Examination under anesthesia, arthroscopy

- Labral signs confirmed by physical examination, MRI, arthroscopy

- With instability

- Without instability

- Instability

- No evidence of instability or labral pathology

- Training error

- Overuse

- Normal adaptation to increased loads

- Abnormal active range of motion

How to Use an X-Ray to Evaluate Shoulder Pain

The appropriate selection of x-ray views is dependent upon the diagnosis being considered. At the very least AP and lateral views are required. With the exception of localizing rotator cuff calcium deposits, these views are inadequate to evaluate injuries and disorders of the shoulder joint.

Patients sent for evaluation with AP and lateral views of the affected shoulder may require additional properly performed views depending on their diagnosis.

While the technique for taking these x-rays is not included on this page, the type of view required for different diagnoses is listed below.

Trauma Series

- True AP view

- Axillary view or True scapulolateral (Y) view

- CT scan may be necessary

Anterior Instability Series

- True AP view

- West Point axillary lateral (prone axillary)

- Apical-oblique view

- Stryker notch view (AP in full internal rotation)

- CT scan

Rotator cuff / Impingement Series

- AP view with arm in IR or ER

- 30-degree caudal tilt view

- Outlet view

Acromioclavicular Series

- Zanca view (10-degree cephalic tilt AP)

- Comparative AP views of bilateral shoulders with and without weights if necessary

- Axillary lateral view

Clavicular Series

- AP view

- 30-degree cephalic tilt view

- 30-degree caudal tilt view

Sternoclavicular Series

- Serendipity view (AP view with a 40-degree cephalic tilt view of both clavicles)

- CT scan

Confirmatory tests include MRI, examination under anesthesia, and arthroscopy. Ability to detect labral signs indicative of a tear is probably the least accurate test for the shoulder. An O’Brien’s test can be used as well as attempts at relaxation and circumduction of the arm overhead with a posterior force stressing the anterior superior labrum. If a patient has signs of a labral tear with clicking or popping or a positive O’Brien’s test, the clinician should try to determine whether the findings are associated with instability, which would have profound implications on type of treatment and recovery time.

In our experience, the physical examination and the MRI are not highly accurate for evaluating labral tears and arthroscopy is the most definitive procedure.

Some patients may not have any signs of labral tears, have no anatomic abnormal laxity patterns, but have “functional” instability, which can be manifested as secondary impingement or internal impingement. Internal impingement is most frequently observed in an overhead-throwing athlete. Secondary impingement is believed to occur from slightly increased laxity of the glenohumeral articulation, which allows riding up of the humeral head and pinching of the supraspinatus in the subacromion space and results in a positive impingement sign.

A small number of patients, particularly athletes, have an entirely normal physical examination, but continue to complain of pain. The examiner should look for training errors in the athlete’s program or chronic overuse injury. Alternatively, pain may be a normal adaptation to increasing loads placed on the shoulder as it accommodates new demands. It should be stressed that repeated physical examinations over time, particularly with highly competitive athletes, are needed to evaluate changing pain patterns, which may highlight the real diagnostic culprit.

For example, multiple diagnoses may be made after an athlete has a contact injury to the shoulder. The patient may have a positive palpation to trapezius, positive pain on the acromioclavicular joint in cross adduction, and an impingement sign. Repeat examination, after addressing these 3 areas in the next few days, may indicate the trapezius pain and spasm are resolved, acromioclavicular joint pain is resolved, but the impingement continues. At this point, the examiner can be more aggressive, if there is no indication of rotator cuff tear, and consider a corticosteroid injection. Conversely, the same patient could present a few days later with no trapezius pain or impingement pain but isolated acromioclavicular joint pain. Therefore, treatment would be directed at the acromioclavicular joint and may include a corticosteroid injection. The examiner must record the positive findings, using the algorithm, and review the clinical picture of problems with the shoulder, addressing each of them individually.

Work-Related Shoulder Conditions

Differential Diagnosis of Shoulder Pain

The evaluation is designed to test for the most common causes of shoulder pain in both athletes and nonathletes.

Differential diagnosis of shoulder pain

- Referred sources

- Neck

- Subdiaphragm

- Ribs

- Sternoclavicular

- Acromioclavicular

- Sprains (I-VI)

- Fractures distal clavicle (I-III)

- Instability — horizontal

- Degenerative

- Osteolysis

- Scapulothoracic bursitis

- Glenohumeral

- Rotator cuff

- Tear (complete vs partial)

- Tendinitis

- Biceps tendinitis/tear

- Impingement

- Rotator cuff

- Adhesive capsulitis — frozen shoulder

- Instability

- Unidirectional — anterior vs posterior

- Multidirectional instability

- Labral tears — anterosuperior Vs Bankart

The key to management of the injured or painful shoulder in the athlete is correct diagnosis. Predominant sports-specific problems are outlined in the following table.

- Neurologic

- Burners or stingers

- Nerve root irritation

- Brachial plexus injuries

- Axillary nerve injuries

- Suprascapular nerve entrapment

- Acromioclavicular osteolysis

- Rotator cuff

- Tendinitis Vs impingement

- Primary (1) Vs secondary (2) impingement

- Internal impingement?

- Glenohumeral instability

- Subluxation dislocation

- Unidirectional Vs multidirectional

- Labral pathology

- Location-associated

- Instability-associated

Importance of an Accurate Diagnosis

When a patient presents with a shoulder injury or pain, it is critical to any treatment that an accurate diagnosis be made. Once the evaluation skills are practiced and mastered, then both conservative and operative options can be addressed. In general, unless absolute indications for surgery are present (ie, rotator cuff tear in an athlete or recurrent instability with Bankart lesion), the physician can begin a conservative program with rehabilitation and activity modification. The physician should understand the role of selective lidocaine and corticosteroid injections to determine and treat subacromial pain syndromes and acromioclavicular joint pain. More detailed treatment scenarios are beyond the scope of this article and can be referenced when needed in major sports medicine texts.

Summary

Knowledge of the shoulder anatomy and the patient’s pertinent history together with using a stepwise approach to examine shoulder pain, as in the algorithm presented, provides a basis for a complete evaluation of shoulder injury. Multiple diagnoses are common in the athlete with shoulder pain. This clinical approach is meant to serve as a building block, which each examiner can modify based on experience and confidence in individual tests for impingement, instability, and labral pathology. New imaging modalities or examinations also can be incorporated in the evaluation and diagnosis.

Key Points

- The examiner should use a stepwise approach to physical examination of the athlete or patient presenting a complaint of shoulder injury, pain, weakness, or restriction of motion. The examination should proceed from the neck to the glenohumeral articulation.

- Impingement syndrome is a mechanical impingement of the rotator cuff between the coracoacromial arch and the humeral head. Arm positions that cause the humeral greater tuberosity to impinge against the inferior aspect of the acromion will reproduce pain in patients with impingement syndrome.

- Diagnostic studies such as MRI and arthroscopy are not substitutes for a thorough competent physical examination.

- The key to management of the injured or painful shoulder is correct diagnosis. The referral of a patient to physical therapy with a diagnosis of “shoulder pain” will not yield the same result as the patient who is sent to the therapist with a more specific diagnosis such as impingement, adhesive capsulitis or instability. The approach taken by the therapist is different for each diagnosis and is guided by the treating physician.

- Many injuries and diagnoses are specific to sports and relatively unique to an individual sport. Repeated physical examinations over time, particularly with highly competitive athletes, are necessary to evaluate changing pain patterns.

References

- Spindler, K, Dovan, T, McCarty, E. Clinical Cornerstone 3(5):26-37, 2001. Excerpta Medica, Inc.