Osteonecrosis of the Knee

Osteonecrosis is the death of bone tissue. There are three types of knee osteonecrosis: 1) spontaneous (occurs without a known cause), 2) post-arthroscopy (occurs after an arthroscopic procedure), and 3) secondary to some other condition such as lupus, use of steroids, or alcohol abuse.

Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee is also referred to as SPONK. It usually occurs in one compartment or section of the knee, while secondary osteonecrosis (caused by disease or medical therapy) affects more than one compartment. The bottom, round part of the femur(thighbone) called the femoral condyle is affected most of the time.

Spontaneous osteonecrosis usually occurs in patients older than 55 years, while secondary osteonecrosis can occur at any age. Women are affected by SPONK three times more often than men. The reason for this is unknown.

Osteonecrosis of the knee is uncommon after arthroscopy. It usually occurs when some form of heat such as laser or other thermal devices were used during the procedure. The patient starts to develop worse pain after arthroscopy than before. Knee swelling is a common feature of this problem. (Dr. M comment: This is one reason that I never use these laser or thermal devices for knee arthroscopy. The other reason is that they are not necessary.)

Diagnosis & Treatment

MRIs are relied upon to identify and diagnose osteonecrosis of the knee. In more advanced cases, a plain x-ray may reveal the problem. Bone scans are only reliable 56 per cent of the time. Osteonecrosis shows up on MRIs 100 per cent of the time. The main disadvantage of MRIs is the delay in findings after symptoms have started. Early on in the disease process, nothing unusual shows up on MRIs. The exact best timing for identifying this condition using MRIs remains unknown.

Once the condition has been diagnosed, then treatment begins. Everything is done to preserve the joint and prevent further breakdown of the bone. Early lesions can be treated conservatively (without surgery). The types of lesions that respond to nonoperative care have no low-density lines deep in the femoral condyles (as viewed on MRI scans) and no defects in the shape of the femoral condyles.

Patients are directed to avoid putting weight on the knee along with activity limitations. They must be patient as this protective process can take from three to eighteen months. Bone resorption may be stopped by the use of medications called bisphosphonates. Knee pain can be managed with analgesics (pain relievers). Treatment with bisphosphonates is fairly new and has not been proven effective for all patients yet. Further study of these drugs must be completed to guide the surgeon in knowing when and how to use bisphosphonates, as well as which patients would benefit the most.

Another newer drug treatment for knee osteonecrosis is tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFA). This substance is injected right into the knee joint. Case reports show rapid (one-week later) improvement in pain and stiffness. Signs of healing are seen on MRIs after only one month.

But when the case is too far advanced or when nonoperative care doesn’t work, then surgery to repair the lesion may be needed. The type of surgery done depends on where the damage is located and how severe it is. The surgeon can drill holes in the bone, a procedure called core decompression. Debridement (scraping the damaged area) followed by bone grafting to replace the missing bone has also been tried.

There haven’t been very many cases treated with these various techniques. So, which one works best and for what types of knee osteonecrosis are also unknown factors. The most information we have is on the outcomes using unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. In this procedure, the surgeon replaces just the half of the joint that’s been affected by the necrosis (rather than doing a full knee joint replacement). Some patients may require a total knee replacement if there is evidence of arthritis elsewhere in the knee or if the knee joint is malaligned due to arthritis or osteonecrosis.

Results reported from a limited number of studies report excellent results with this technique. Researchers consider the unilateral knee arthroplasty a very promising approach, but once again, more studies are needed to confirm these results and to see what happens in the long-run.

Right now, we only have limited information and understanding of what causes knee osteonecrosis and how to treat it. At the present time, research efforts are directed toward finding ways to preserve the joint, rather than replace it. Nonoperative treatments with new methods of tissue engineering may eventually provide a breakthrough in the treatment of this disease.

Bisphosphonate treatment for knee osteonecrosis offered rapid pain relief and radiological consolidation of the osteonecrotic area, according to Swiss researchers.

In a prospective, researchers studied how bisphosphonate treatment affected 28 patients with spontaneous or arthroscopy-induced knee osteonecrosis. Patients had osteonecrotic lesions and bone marrow edema. Twenty-two patients developed osteonecrosis after knee arthroscopy, and six patients developed spontaneous osteonecrosis.

First, patients received 120 mg of intravenous pamidronate in three to four perfusions over a 2-week period, followed by 70 mg/day of the oral bisphosphonate alendronate for 4 to 6 months.

The results showed that bisphosphonate treatment was beneficial to patients. Bisphosphonate treatment quickly relieved pain, with Visual Analog Scores (VAS) dropping from 8.2 ± 1.2 at baseline to 5.02 ± 0.6 at 4 to 6 weeks postoperative (P < .001). The VAS decreased by 80% at 6 months (P <. 001). Fifteen of 28 patients had complete symptom resolution at 6 months follow-up; 6 patients had minimal symptoms (VAS 1 or 2).Magnetic resonance imaging revealed that in 18 of 28 patients, bone marrow edema completely resolved. The edema was significantly reduced in the remaining patients. In some cases, the researchers observed complete resolution of the osteonecrotic area; in others, they saw demarcation with sclerotic changes.

Two patients had an unsatisfactory treatment effect; they both underwent arthroplasty.

The observations of the study are certainly consistent with the antiresorptive mechanism of bisphosphonates. In disorders of which the pathophysiology is dependent on turnover of bone or substantial osseous resorption, bisphosphonates present a potential therapeutic strategy.

However, without a true control group (as the authors note), this study does not rigorously show that the medication altered the natural history of the ON.

I perform many knee arthroscopies (~150-200+) every year and have done so for 20 years. If we see a problem post-operatively, the most common problem we may see in patients with knee osteoarthritis, is a continuation or increase in their knee pain from the arthritis. The pain from their meniscus tear may be improved, but how the arthritis will respond to an arthroscopic surgery can be unpredictable.

Post Knee Arthroscopy Osteonecrosis

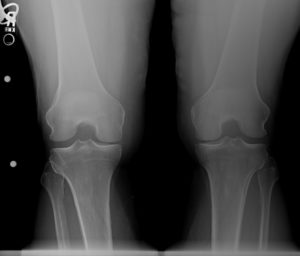

Post knee arthroscopy osteonecrosis is more uncommon but below are some examples of my own patients over many years who have had this problem. They have, in turn, gone on to require a knee replacement with good results.

|

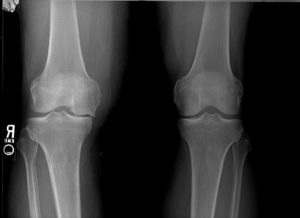

| Here is that patient’s x-ray many months later showing loss of the medial joint space and collapse of the femoral condyle due to osteonecrosis. He is bone on bone with collapse of the medial joint. |

So what’s the point.

Under the best of circumstances, even with an experienced surgeon, a simple knee arthroscopy for a meniscus tear can have develop problems. While the risk of surgery, like a knee scope, is relatively low, the risk is never “zero”.

We do not really know what causes post arthroscopy osteonecrosis in these knees.

The references for the science are below. The patients are mine.

Thanks,

JTM, MD

References:

Maria S. Goddard, and Harpal S. Khanuja, MD. Special Focus. Knee Reconstruction. Osteonecrosis of the Knee. In Current Orthopaedic Practice. January/February 2009. Vol. 20. No. 1. Pp. 65-72.a

Bisphosphonates may offer benefit for knee osteonecrosis

Kraenzlin ME, Graf C, Meier C, et al. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosoc. DOI 10.1007/s00167-008-0673-0