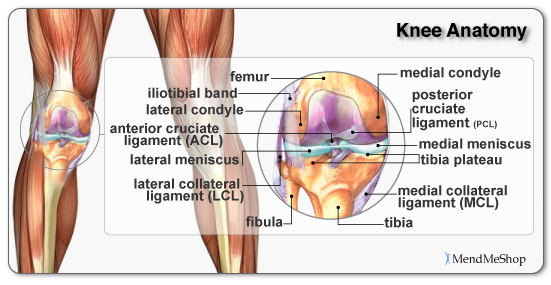

The knee (tibiofemoral) joint is the largest and one of the most complex joints in the body as it allows you to flex and extend your knee as well as rotate it horizontally. The knee provides both strength and flexibility while being loose enough to allow the freedom for quick movements and changes in directions. It is not the bones inside the knee that provides stability, instead it is the soft tissue (tendons, ligaments, muscles, menisci) that hold the femur (thigh bone), the tibia (shinbone), the fibula (the slender bone in the lower leg) and the patella (kneecap) together at the joint.

The knee cap (patella) is a bone embedded within a tendon that rests over a groove at the bottom of the rounded femur and the top of the flat tibia. It protects the bones and soft tissue in your knee joint and slides when your knee moves, giving leverage to your leg muscles. The tendons in the knee are tough cords of tissue that connect muscle to bone and help control movement of your joint. The upper leg muscles provide your knees with mobility (extension, flexion and rotation) and strength. The quadriceps muscles (located on the front of your thigh rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, vastus intermedius) straighten your legs, and the hamstring muscles (located on the back of your thigh semitendinosus, semimembranosus, biceps femoris) bend your knees.

As well as providing stability, the tendons, ligaments, articular cartilage, meniscus and other soft tissue in the joint provide cushioning and protect the bones. A type of slick, hard but flexible tissue known as articular cartilage (also called hyaline cartilage) covers the surface ends of the tibia and femur at your knee joint, allowing them to move easily against one another. It is generally 1/8 to 1/4 inch thick. A thick, stringy, egg-like fluid (synovial fluid) found inside the knee capsule, lubricates your knee joint and, along with the meniscus and articular cartilage reduces friction.

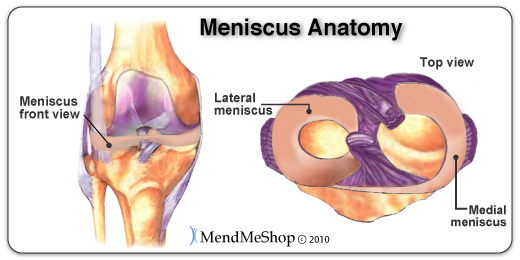

The soft tissue structure in the knee includes 2 menisci, the medial meniscus (located on the inside of the knee) and lateral meniscus (located on the outside of the knee). These crescent-shaped pads of fibrocartilage rest on the tibial condyles (rounded ends of the tibia bone) and form a concave surface for the femoral condyles (rounded ends of the femur bone) to rest on. These cover approximately 2/3 of the tibia surface and are thicker on the outside and thinner on the inside appearing triangular in cross section. They fill the space between the leg bones and cushion the femur so it doesn’t slide off or rub against the tibia.

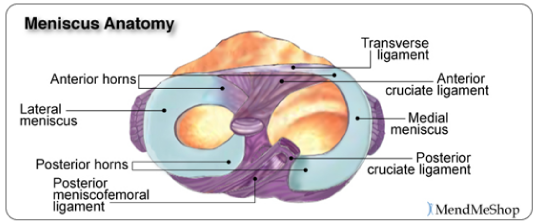

The two menisci are joined together within the knee joint by the transverse ligament. The menisci also attach to leg muscles which help the menisci maintain their position during movement. The semimembranosus and quadriceps attach to both menisci. The lateral meniscus attaches to the popliteus below the knee and the femur via the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL). On the inner part of the knee, the ends of the menisci (known as the anterior and posterior horns) are attached to the tibia and joint capsule and along the exterior edge of the meniscus by the coronary ligaments. These ligaments are loose which allows the meniscus to pivot freely. However, the medial meniscus does not move as freely in the joint as the lateral meniscus and as a result is torn more frequently.

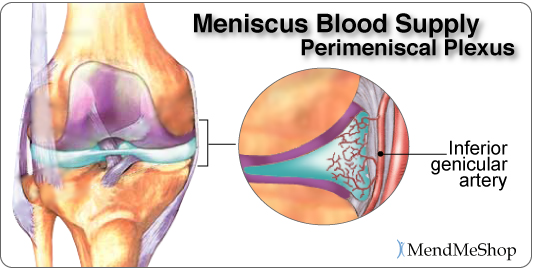

The blood flow to the menisci comes from the inferior genicular artery. This artery supplies blood to the perimeniscal plexus which provides oxygen and nutrients to the synovial and capsular tissues around the menisci and within the knee joint. The coronary ligaments attached to the meniscus, transport the blood from the perimeniscal plexus (network of blood vessels) into the peripheral of the menisci. The anterior and posterior horns of the menisci also receive a good amount of blood as they are covered by a vascular synovium. The interior part of the meniscus is avascular, having no direct blood supply.

The Function of the Meniscus

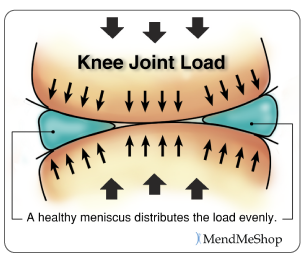

The menisci play a very important role in the proper working of the knee. Essentially, they serve as cushions to decrease the stress caused by weight bearing and forces on the knees. They work like shock absorbers, supporting the load by compressing and spreading the weight evenly within the knee. Even while walking, the pressure put on the knee joints can be 2 – 4 times your own body weight; when you run these forces increase up to 6 – 8 times your body weight and are even higher when landing from a jump. By increasing the area of contact inside the joint by nearly 3 times, the menisci reduce the load significantly (dispersing between 30 and 55% of the load).

As weight is applied to the meniscus they are compressed and are forced to extend out from between the femur and tibia. However, the circular design of the menisci provides circumference tension (referred to as ‘Hoop Stress’) to resist this extension and provide stability as the load compresses. If the meniscus is torn at the peripheral rim, circumference tension is compromised and the meniscus loses its ability to transfer the load and the joint begins to suffer. In fact, if part of the peripheral is removed or the tear extends to the periphery, the load on the knee joint may increase by up to 350% causing stress and pain. However, if the tear remains on the interior without disrupting the periphery of the meniscus, the meniscus is still able to disperse the load without stress and pain.

The menisci also assist with the proper movement (arthrokinematic) of the femur and tibia during flexion and extension. Flexion and extension images here They help stabilize the knees when in motion, reduce friction within the joint, and lubricate and protect the articular cartilage surrounding the tips of the bones from damage due to wear and tear.

What is Fibrocartilage?

The menisci are composed of tissue called fibrocartilage which is tougher and contains more fiber than other types of cartilage in the body. The collagen fibers are woven into dense tissue that is resistant to stretching and extending in various directions. This makes fibrocartilage excellent for cushioning the knee joint that is required to move multidirectionally.

The amount of blood vessels in the fibrocartilage throughout the meniscus varies. The outer one-third of the meniscus is vascular, which means there is an abundance of blood vessels to allow blood to the area. The central part of each meniscus has fewer blood vessels and the inner third does not contain any. As a result, a tear on the outer peripheral of the meniscus can heal faster than one on the inner portion. Tears in the innermost part of the meniscus may not heal completely due to the lack of blood supply. Without proper nutrition (blood supply) the menisci may partially disintegrate resulting in less cushioning and protection within the joint. Proper blood flow ensures nutrients and oxygen reach the area and metabolic waste is removed from the fibrocartilage. When functioning properly, the knee joint naturally receives blood flow through movement and the pumping action of body weight shifting from knee to knee. However, other therapies such as Ultrasound and Blood Flow Stimulation Therapy will promote more blood flow, even when the knee is at rest. Greater blood flow results in faster and more complete healing when meniscus or ligament damage occurs.

Knee Ligaments

Ligaments are strong, elastic-like tissues that connect bone to bone and provide stability and protection to your knee joint by limiting the forward and backward movement of the shin bone. The knee has 2 collateral (parallel) ligaments and 2 cruciate (crossing) ligaments. The medial collateral ligament (MCL) and the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) provide support to the knee by limiting the sideways motion of the joint and resisting extreme rotation in a partially flexed position. The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) stabilize the knee by limiting the rotation and the forward and backward movement of the joint.

The MCL is the most commonly injured of the collateral ligaments. Injury is often a result of a blow to the outer side of the knee during sports. Since the MCL is attached to the medial meniscus, damage to the medial meniscus often occurs when the MCL is injured during a hard hit to the knee. The cruciate ligaments (ACL and PCL) are strong and thick providing stability to the joint. Together they work to prevent extreme knee motions of any kind. As a result, any damage to a cruciate ligament can cause noticeable instability in the knee. An ACL injury, the most common cruciate ligament injury, occurs when the knee is locked with the foot planted and the knee is twisted quickly. Athletes required to make sudden directional changes or to slow down quickly as well as those in contact sports are at high risk for ACL tears. Minor tears may go unnoticed immediately and will appear a few hours later with pain and swelling. More serious ACL tears are accompanied by severe pain and often a popping sound. The knee may feel as though something has snapped and walking or bending the knee is usually impossible.

The medial collateral ligament (MCL) and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) are ligaments of interest to meniscus tear sufferers because meniscus tears that occur due to force trauma are sometimes accompanied by tears to the MCL and/or ACL. When the meniscus, MCL and ACL are injured in combination it is referred to as the “unhappy triad”.

What Happens When the Meniscus is Injured?

A meniscus injury is one of the most common knee injuries. Menisci tend to get injured during movements that forcefully twist your knee while bearing weight (this is very prevalent in younger populations) or they tend to grow weaker with age, and tear as a result of minor injuries or movements. When your meniscus is damaged and/or torn, it starts to move abnormally inside the joint, which can cause it to become caught between the bones of the joint (femur and tibia). Your knee then becomes swollen, painful and difficult to move. These injuries can be difficult to heal because blood supply (which helps your body heal itself) is often limited to the outside edge of the menisci.

Once you have a meniscus tear, you have an increased risk of developing knee arthritis because these shock absorbers are weakened. They slowly wear away with knee movements and are not able to protect your articular cartilage on the surface of the knee joint as much as before.

While some meniscus tears can be repaired, most cannot be fixed. The torn piece is removed through the arthroscope in the operating room. The tear itself and the removal of the loose piece result in increased forces on the surfaces of the joint which then can lead to a progression of arthritis. In a small number of cases, pain from the arthritis can progress after surgery to remove the torn meniscus. It is the tear, not the surgery, that leads to the continued pain and progression of arthritis.

Patients must understand that, if they have a torn meniscus in the face of arthritis, their pain may not be completely resolved by an arthroscopic surgery. In a small number of cases, the pain from the arthritis may even increase.

In the USA, 61 of 100,000 people experience an acute tear of the meniscus at some point in their life (850,000 meniscus surgeries are performed in the USA each year, estimates indicate that at least twice this number of meniscus procedures are performed internationally). Health professionals used to believe the meniscus had no function and removed it if injured, however we now know it plays an integral role in knee joint mechanics and function.

Thanks,

JTM, MD